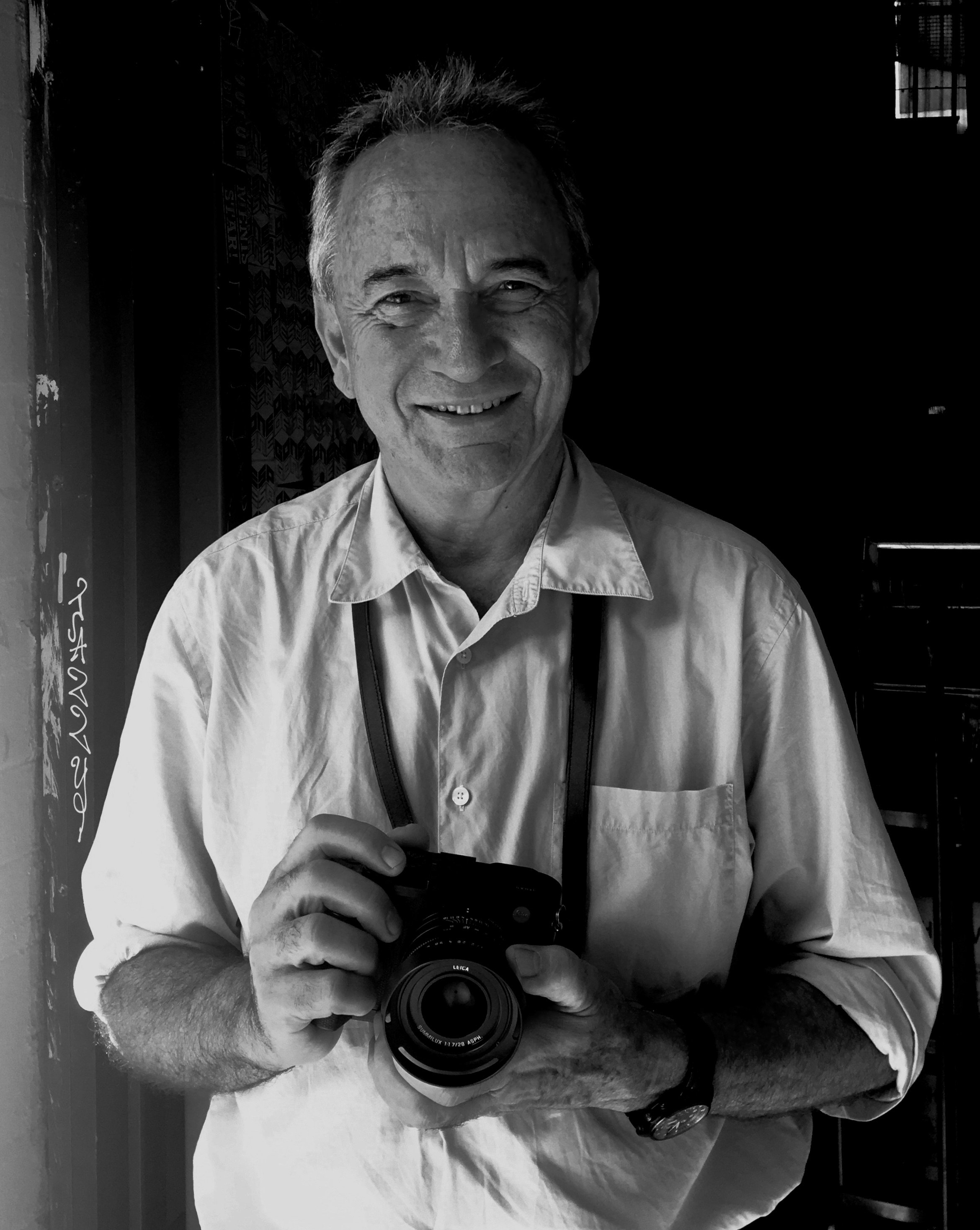

After a one-day workshop conducted for the New England Writers’ Centre in northern New South Wales, I agreed to answer a few probing questions about my life and writing methods. The results were published in the Autumn 2019 edition of the NEWC newsletter, The New England Muse.

Can you tell us about yourself?

I was born and grew up in Brisbane, in sub-tropical Australia. My Greek father and Anglo-Australian mother ran corner shops where, incredibly, people bought all their weekly groceries and fruit and vegetables. (Supermarkets didn’t exist.) Every week my brother and I went to the Saturday matinee at the movies, two movies, then we returned for the night double with my parents – four films a week, 200 a year, roughly 2000 over my childhood. I didn’t read novels until I was about fourteen, then I started with Grahame Green’s The End of the Affair. The librarian was a bit stunned. That’s when I decided to be a writer. Leaving high school I scored a journalism cadetship with the ABC and, one way or another, I’ve made a living since as a storyteller, in fact and fiction. I love it, though part of me still wishes I’d been an architect.

Can you tell us about your style of writing?

I’m big on structure, on the possibilities of structure: sentences, paragraphs, chapters, books. (An architect with words.) Sometimes I play with time. My writing tends to be simple (probably reflecting my years as a radio journalist) but occasionally I’m prone to poetry. It’s impossible for any writer to describe their own style, it’s like asking ‘What sort of person are you?’ Best left to others to decide. I do have my writing quirks: one of my best (or worst) is trying never to end a sentence on a capitalized letter. For instance, I would avoid writing, ‘After a week, he went to Berlin.’ Which is a perfectly good sentence. I accept it’s insane. This probably explains why my novels take so long to write.

Is your personality reflected in your work?

I guess there’s a template with my name on it. From first draft to last the text changes, often dramatically, but there’s always a remnant in there that I know could only come from my head. But where inside that head it comes from I have no idea. It’s not uncommon for me to re-read my work and say, ‘Did I actually write that?’ Because I have no memory of doing it. I’ve changed in the interval between when I wrote it and now, I’m not the same person who wrote that.

How do you overcome creative blocks?

I don’t really suffer creative blocks, I just write. I’ve got maybe fifty outlines for different novels and movies on my laptop, and more material than I know what to do with. Like most writers I get restless at the keyboard after a while and find some excuse not to write, usually cooking or catching up on journalism - The New York Times, the BBC. I can be at the desk for four or five hours if I’m in the zone. For a break I work out with weights or go for a swim. Q: Is writing physically demanding? A: Only if you’re doing it right.

Can you briefly explain your creative process?

In my thirties I began collecting concepts and ideas for books. Now that they’re on the computer, I keep folders for each project and add material whenever I see something relevant. I’m forever cutting and pasting articles, interviews, images. I spend maybe 20 per cent of my working day on this, even though most of the projects will never be realized. (I figure there has to be a spill-over effect on current projects.) My writing begins as a core idea surrounded by a collage of raw material, which I gradually shape into what’s needed to bring the idea to life. I also keep paper scraps on my bedside table and scribble ideas in the dark hours. My record was 23 scrawled-on scraps in a creative burst one night. (About 60% intelligible in the morning.) It sounds pretty chaotic but it’s a process I’ve grown accustomed to over the years.

Lastly, any words of wisdom you would like to share?

I burned my pile of ‘how to write’ books long ago, but keep a few core mantras in my head. The first is Maupassant’s advice: ‘Put black on white.’ Get something, anything down. Don’t wait for perfection or you’ll be waiting forever. (That applies to almost everything in life.) The extension of that is, ‘All writing is rewriting,’ because rarely is the first draft there. The biggest ‘trick’ (and let’s face it, all writing is the creation of illusion) comes from the late, great Philip Roth: ‘The slow release of vital information.’ Or as the screenwriter William Goldman said, ‘Make ’em wait, make ’em wait, make ’em wait!’ The reveal is at the core of all great storytelling.